The Invisible Earth

This is a monthly newsletter about my current artwork, ideas, influences, past projects, and upcoming exhibitions, often with some personal content thrown in. I will also include announcements when prints or originals are up for sale.

It’s been a productive autumn for me. I've made eight new paintings this month: six small "Iterations" (still-lifes—see gallery above) which repeat a single object from multiple perspectives, and two large Non Sequitur paintings. My Non Sequiturs are of randomized pairs of subjects, with no obvious relationship to one another.

The Non Sequiturs were two of the most challenging paintings I have ever made, and in very different ways. In "Bird Bridge", I felt like I was trying to construct a relationship from scratch. The subjects may have been so generic that the scope for imagination was correspondingly immense. In any event, the Bird-Bridge connection felt like something I planned out and built by hand, on my own. I love the result, it’s just that the process felt like an act of engineering.

Bird Bridge, 15” x 20”. Ink and watercolor on paper.

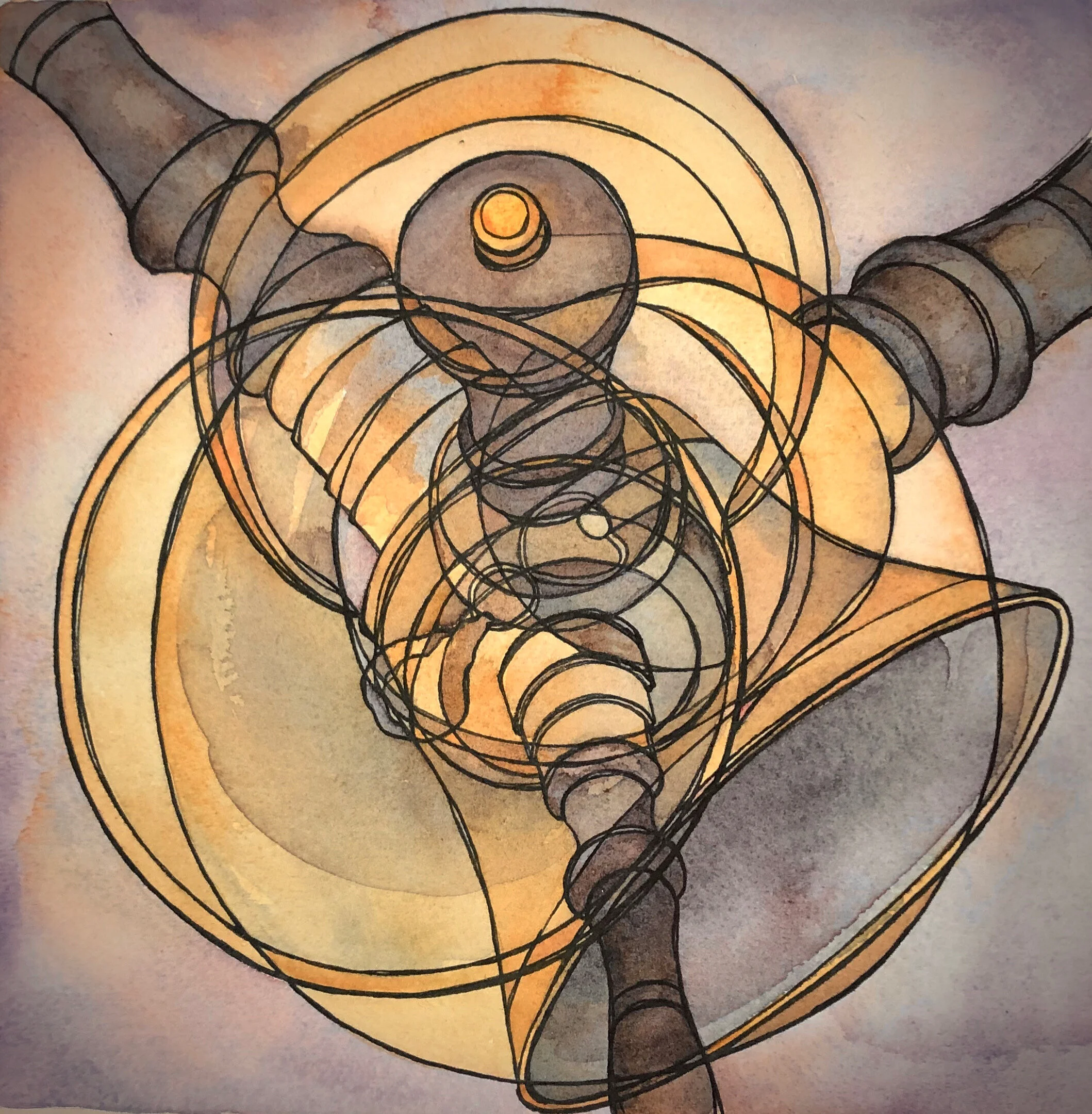

In "Moon Citadel" the connection was already there. All that was really left for me to do was to try and find the logic behind a relationship that already existed.

I guess I've always been partial to stories that write themselves.

The citadel had to be the great Citadel of Aleppo in Syria, illuminated by the full moon, as I saw it at night in the Northern Galilee in 2012—the closest I have ever been to Aleppo.

I have only an indirect connection to Syria. From 2008 - 2012, a dear friend of mine was studying and working in Damascus. Through her work and experiences in Syria, I acquired a persistent interest in the country's history, politics, and people.

There is something that feels fundamentally wrong about making art about a culture with which I am not personally involved. And yet my own existence stands, directly, on the histories, natural resources, work, cultures, and human misery of the great invisible Elsewhere. Politically, historically, socially, economically, and not least from a moral point of view, I am connected to Syria, even if this relationship is invisible to me.

This very invisibility is, I think, a fundamental problem with the cruel systems at work in the world today. I do not see where my food comes from. I do not see the conditions inside the factories that make the clothing I wear. I do not see the many ways I profit financially from the wars and political upheavals around the world, merely by virtue of the way the systems work.

To my mind, this is where art comes in. Art isn’t merely a luxury hobby for rich gallery patrons, it’s a fundamental part of all human cultures, which has been with us as a species since at least the beginning of recorded history. The purpose of art is to draw our attention to that which is beyond our own individual experience. Storytelling lets us see into others’ lives, and composers and choreographers are able to convey profound emotions to people they have never met. Poets seed images and ideas. Visual artists transport us—to another place, another time, another mind, another universe. Art shines a light on important things we are otherwise unable to see. Only when our world is visible can we begin the work of change.

The Moon is in a tidal lock with the Earth, meaning that it has the same rotational period (day) as its orbital period (year). A tidally locked satellite always shows exactly the same face to its parent planet, which is why we never see the dark side of the Moon from Earth.

In other words, the Moon never looks away.

Unlike the Moon, we as human beings can look away from war and suffering and death, but art holds our attention, enchants us, makes us need to know more. I believe that not looking away—tidal locking with as much of our world as we can—is the critical first step. We must pay attention, and we must chase the beauty and meaning we find to the end.

We must listen to those voices we have been taught to ignore. We must gaze into the invisible places of the Earth.

Moon Citadel, 15” x 20”. Ink and watercolor on paper.

The Aleppo Citadel has origins dating back to at least the third millennium, B.C.E. Even after the city extended beyond the walls of the Citadel, it continued to act as a sanctuary for its people during times of attack. The old city of Aleppo was the home of many ancient Semitic peoples, and changed hands between the Greeks, the Romans, the Byzantines, and finally the Muslims, who eventually expanded into the vast Ottoman Empire. After the Ottomans’ defeat in 1920, the Citadel came under the administration of the French Mandate until 1945, when a new state was created.

The Syrian Civil War broke out in 2011, after peaceful civilian protests drew violent reactions from the Syrian Army. In 2012 the Citadel of Aleppo was seized as a military base for the Syrian Army, from which they could safely attack the surrounding city. In 2016, the fighting ended in Aleppo, and the Citadel reopened to the public in early 2017, with repairs in progress.

Before the war, the Citadel of Aleppo was one of the most visited monuments in the Middle East, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors from all around the world. The Citadel is part of the Old City of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and thereby entitled to international resources for protection and restoration.

Further Reading:

U.S. Sanctions Strangling Rebuilding the Old City of Aleppo

The Aleppo UNESCO World Heritage Site